The screwball pitch: what it is, how to throw it & pitchers who do

by Fred Hofstetter on September 8, 2019The history of the screwball pitch in baseball is slippery. How it started, who throws it and even how to grip it is all up for debate.

Baseball evolves—slowly. Relative to the world swirling around it, the game is an anchor in American history. The constant amidst a whirlwind of unpredictable variables. However, pull out the perception and you’ll find a game that doesn’t look much like the original. There is always a mini-era in progress and it’s difficult to pinpoint it in the moment.

Recently the evolution of major league baseball quietly started abandoning the junkballer. The improviser. The twirler. When play-by-play guys start dropping words like cagy, crafty or moxy. Jamie Moyer, Randy Wolf, Bronson Arroyo, Paul Byrd. The everymen of the baseball world. Modern baseball favors velocity, spin rate, clean mechanics and specialty. Finesse pitchers can survive, but only the best of the best. The leash on a curiosity is short, and the leash on a superathlete who lights up a radar gun is long. Unusual pitches from the hand of junkballers like the knuckleball, palmball, forkball and eephus are supplanted by really good fastballs, sliders, curveballs and changeups.

Screwballs have never been commonplace. But it’s certainly not a screwballer’s game anymore.

Screwball movement: what the pitch is and what it looks like

The screwball is sometimes referred to as a reverse curveball. It’s a breaking / off-speed pitch hybrid that moves away from an opposite-handed batter; a right-handed pitcher’s screwball breaks away from a left-handed batter.

Picture a curveball and reverse it. That’s just about what a screwball does.

This video shows some really good behind-the-plate shots of current Tampa Bay Rays prospect Brent Honeywell throwing screwballs in the minors. Here’s a GIF of a screwball pitch in slow motion:

You’ll have trouble finding high quality, easily accessible footage of a screwball. Most of its worthy practitioners are long dead. More on Honeywell later.

How to throw a screwball

What makes a screwball unique is the pronation of the arm as it’s thrown. Instead of letting your arm and wrist fall straight down after release, you actually have to turn your arm to the outside upon release (for right handers, palm facing right – for left handers, palm facing left). This video shows the arm motion plainly. The pronation creates the “reverse” curve breaking towards same-side batters.

The obvious question is If curveballs are so popular, why doesn’t anybody throw a screwball if it’s the same thing only the other way?

That’s because “reverse screwball” isn’t really covering it. Not only is a screwball more difficult to throw, it doesn’t break quite as sharply as a curveball or similar breaking pitch.

The screwball vs. other similar breaking pitches

Although the screwball is often described as a reverse curveball, it’s not a perfect designation. Good curveballs, sliders and slurves typically break sharper than a screwball.

The screwball occupies some middle ground between breaking ball and off-speed pitch. Look on Wikipedia and you’ll see it categorized as a breaking pitch.1 Historically the screwball is associated with the “fallaway” or “fadeaway” pitch, which makes it sound much more like a unique kind of changeup.

This might be a jack-of-all-trades, master of none situation.

- Screwball vs. circle change. The more I read about screwballs the more I think this is its closest comparison and the reason we just don’t see screwballs anymore. The break and speed is very similar but doesn’t require pronation of the arm.

- Screwball vs. changeup. The screwball features some “falling away” break you won’t get with a traditional straight changeup, and they tend to be slower.

- Screwball vs. splitfinger fastball (splitter). Splitters usually drop sharply straight down and carry a lot more speed than a screwball. There’s typically a little less tail on a splitfinger than a screwball.

- Screwball vs. 2-seam fastball. The 2-seam fastball does feature some subtle pronation to create arm-side break like the screwball but relies more on fingertip pressure and late darting break at a fastball speed.

- Screwball vs. sinker. The sinker is very similar to the 2-seam fastball except it generates more downward action. Its key characteristic is the late downward break rather than the arm-side tail and change of speed, unlike the screwball.

- Screwball vs. curveball. The screwball is often regarded as a reverse curveball since it breaks in the same manner only the opposite direction. However, the arm action couldn’t be more different.

- Screwball vs. knuckleball. The knuckleball is in a junkballing league of its own. If a knuckleball breaks like a screwball it’s just a coincidence. Nobody knows where a good knuckleball will break. The thing doesn’t spin.

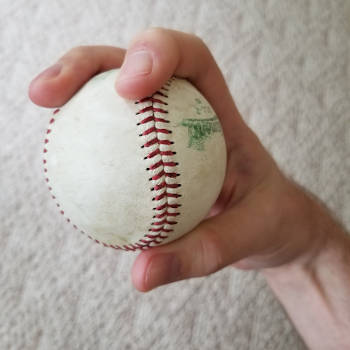

The screwball grip

Unsurprisingly there is no real consensus. Because the pitch is so unorthodox pitchers seem to treat the screwball like their version of the screwball, which results in many different variations. Some of the most common include:

- Something like a sinker/two seamer. For pinpoint control and less of a velocity differential you might be most comfortable with a two-fingered grip and let the forefinger run the show:

- Almost like a circle change grip, with the ring finger split off the seam:2

- Straight up circle change grip – just pronate upon release:3

Ultimately as long as there’s primary pressure along a seam and pronation upon release, something like a screwball will result. Some like the changeup feel, some like the fastball feel.

History of the screwball pitch: how it began

The origins of the screwball are murky. Tracing its usage and estimating its first practitioners is tracking a jackalope. Fuzzy legends, borderline mythological figures and hearsay. Historical testimony wields overlapping terminology and conflicting definitions. Rob Neyer notes 1880s star Mickey Welch was once credited with throwing the first screwball, but isn’t convinced given the fogginess of the source:

“In a recent Sporting News book titled Heroes of the Hall, Ron Smith wrote, ‘When asked the secret of his success, Welch smiled and attributed it to drinking beer. More likely it had to do with the fastball, curve and changeup he mastered while carving up hitters – and an unusual screwball he might have been the first to throw.’”4

Neyer names Charlie Sweeney as a possible early screwball wielder, who is regarded as the father of the “fadeaway.”5

However, baseball historians typically name an all-time great as the originator of what we know as the screwball.

Pitchers who have thrown a screwball

Prominent screwballers run the gamut from hall-of-famers to journeymen big leaguers to obscurities and footnotes.

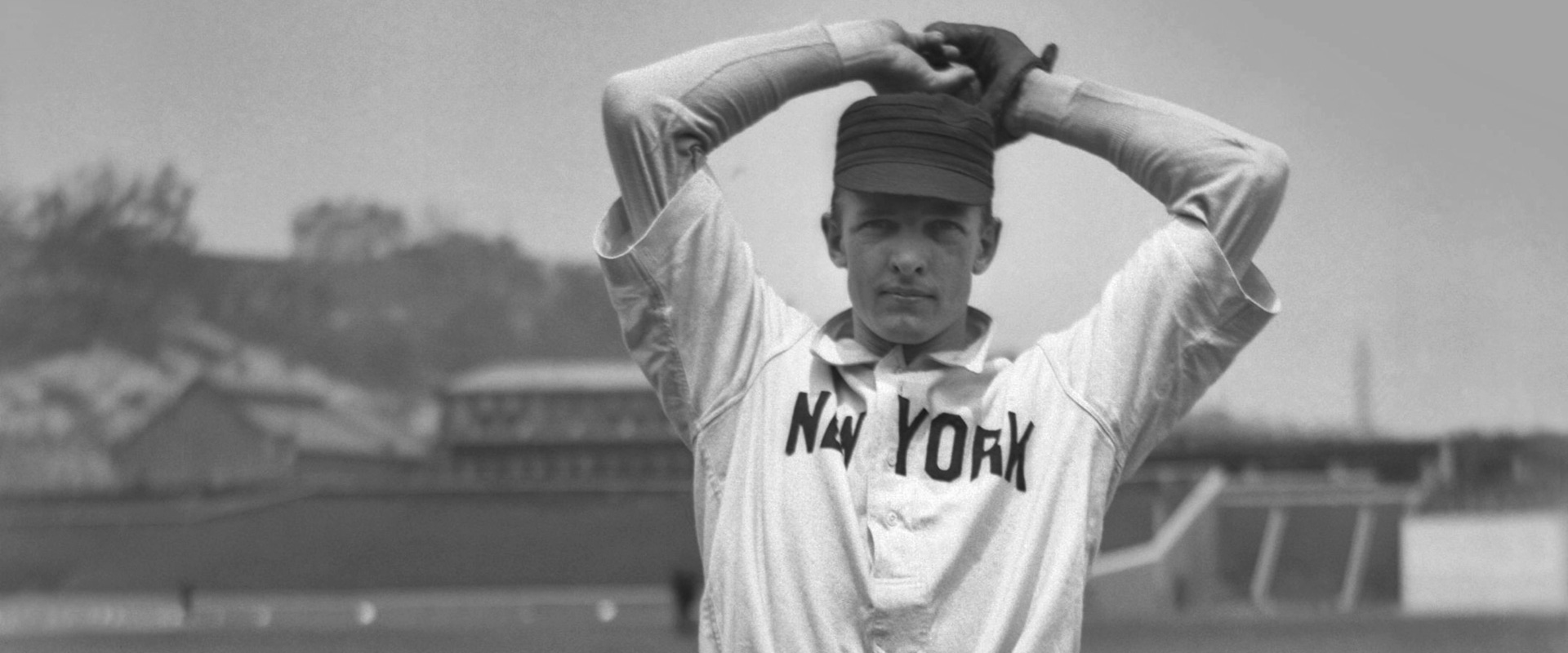

Christy Mathewson

Christy Mathewson was a nonfiction Captain America. The “Christian Gentlemen” was regarded as the “perfect hero for his age” and Connie Mack called him the greatest pitcher who ever lived.6 Recollections of Mathewson’s nobility are borderline cartoonish. Mathewson wouldn’t give interviews to sportswriters he knew cheated on their wives.7 Bill James listed him as the 7th best pitcher of all time in his 2001 Historical Baseball Abstract, quipping “I would have liked Christy Mathewson” and citing this quote from Larry Doyle:

“…if you wanted to find Christy Mathewson in spring training, all you had to do was look for a group of rookie pitchers. Christy would be in the middle of them, trying to show them how to pitch successfully in the major leagues.”8

Mathewson was more than a model citizen for American youth. He is regarded as one of the first to use the screwball—and certainly the first to use it routinely with a lot of success.

Here’s how Christy Mathewson describes a “fallaway”: which many really smart baseball people believe is his name for what we know as a screwball:

“The fallaway, which I have used, if I may be pardoned for saying so, with greater effectiveness than any other pitcher, is an exceptionally slow ball, and calculated to deceive the greatest batter. As it rushes toward him it looks like a fast high ball. Six feet from him when it begins to drop, it has the appearance of a slow drop ball. And then as he swings, he’s straddling in two directions at once.”9

Mathewson defined his own pitches with language you don’t hear in 2019: slow ball, drop curve, out curve, rise ball, spit ball—and fallaway.10 You could easily read his description of the fallaway as a changeup. Unfortunately Mathewson never said something like and then I pronated my arm upon release in a really screwed up kind of way. A wholesome Christian gentlemen would never use such foul language.

Armed with the fallaway and a litany of other plus pitches Mathewson put together one of the best careers in baseball history, amassing a 2.12 ERA (he led the league 5 times), 2.26 FIP (led the league 8 times), one World Series title and 373 wins back when those mattered a lot more.

It would be just over a decade after Mathewson’s retirement when the next Hall of Famer would feature the screwball and spend a career baffling hitters with it. But his legacy may have done more harm than good for the pitch.

Carl Hubbell

Tyler Kepner calls Carl Hubbell “at once the best and worst advertisement the screwball ever had.”11 Hubbell’s long and storied career is both highlighted and blemished by the awkward twisted appendage that hung from his left shoulder after his pitching days.

No pitcher ever leaned harder and depended more on the screwball and the repetitious pronation of the arm that comes with its heavy use.

Legendary manager John McGraw had the unique pleasure of managing both Christy Mathewson and Carl Hubbell. When a scout shared a concern about Hubbell’s use of the screwball and what it could do to his arm, McGraw laughed it off. He had seen Mathewson master the pitch no worse for wear—”When Matty was pitching it, they called it a fadeaway and it never hurt his arm. If there isn’t anything wrong with him, I’d like to know more about him.”12

He would.

Hubbell would become one of the best pitchers of all time for McGraw’s New York Giants, amassing a record of 253-154 over 16 seasons with an ERA of 2.98.

In the four seasons covering 1933-1936, his age 30 through 33 seasons, Hubbell put together a remarkable stretch highlighting his Hall of Fame career. He threw 300+ innings apiece, totaled a 2.38 ERA overall and picked up two MVP awards (1933, 1936). The mysterious screwball was no mystery to a league full of batters left shaking their heads in the wake of his brilliance.

His tremendous success came at a cost. The screwball wrecked his arm.13 After his pitching career ended Hubbell spent the rest of his life permanently in physical pain, resting a backwards left arm at his side, palm out and bent.

Sportswriter Jim Murray remarked “The screwball was not really a pitch, it was an affliction.”14 Perhaps. You could say the screwball afflicted Carl Hubbell with an unforgettable Hall of Fame career we’re still fondly remembering nearly 80 years past its end.

A relic of a bygone era of rubbing-dirt-on-it, for certain. Don’t hold your breath waiting for the next Carl Hubbell—or the next Hall of Fame screwballer.

Brent Honeywell

Given the screwball’s correlation with destroyed superarms, the economics of player contracts and the growing use of acceptable substitute pitches (splitters, circle changeups), adding a screwball to the arsenal in 2019 doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. Very few recent ballplayers have adopted it as a featured offering much less drop it in once or twice a game to keep hitters on their toes.

The rare exception is Brent Honeywell. Scroll up a ways and you can see him throwing a screwball (from the batter’s perspective).

Unfortunately Honeywell is doing no favors for anyone out there hoping to defend the screwball against the critics who stress its danger to pitchers’ elbows. After undergoing Tommy John surgery in February 2018, Honeywell fractured a bone in his elbow connected to the UCL while throwing a pitching during a bullpen session in June 2019.15

With two lost seasons after back-to-back elbow surgeries, the 24-year old has a long way back to start knocking on the big league door again.

Honeywell may be the screwball’s last hope. Nobody else appears eager to carry on the legacy.

Warren Spahn

Spahn is one of those who is often attributed with throwing a screwball, but it may have just been a circle change. As Neyer describes it:

“While everybody knew that Spahn threw a great screwball in the latter part of his career, Spahn himself often denied throwing a screwball at all. And in fact, it seems likely that he was actually throwing the pitch that’s now known as the Circle Change.”16

There are a lot of pitchers in this category – especially back in the day where these sorts of things weren’t documented as well.

Daniel Herrera

Herrera was one of the rare 21st-century era pitchers to consistently feature the screwball. The diminutive left-handed reliever was a rare 45th round success story, putting together a couple effective seasons in the Cincinnati Reds bullpen in 2009 and 2010. He probably couldn’t have done it without the screwball.

He struggled to generate any downward break when throwing a conventional changeup and discovered that by pronating his wrist the opposite way he could get the diving movement he was looking for—essentially training himself to throw the screwball without really realizing it.17

Given its fallaway movement away from right-handers, you might think Herrera would show some reverse splits, but not so—right handed batters OPS’d .949 vs. Herrera vs. a .588 clip from lefties over the course of his career.

Back in 2008 Mike Fast put together an excellent deep dive into Herrera’s repertoire. Even casual baseball fans need a little proof when they hear about a pitcher allegedly throwing a screwball.

Hector Santiago

Santiago might be the screwball’s most public modern screwball practitioner. He was the feature of a New York Times article on the screwball a few years ago. You can read it here.

Because he also throws a changeup with similar break and speed it’s hard to tell what’s a screwball and what’s a changeup. Over the last 3 seasons (2017-2019) Brooks Baseball has only logged 5 screwballs total from Santiago compared to 799 changeups—although in a single start with the Twins back in April 2017 Santiago himself said he threw 7 screwballs in one outing.

Santiago is still kicking it in the big leagues as a reliever with the White Sox as this is written towards the end of the 2019 season. If it wasn’t for Santiago the league would be 100% screwball-free.

Paul Byrd

It’s no surprise longtime junkballer Paul Byrd makes the list. Byrd was an old-school throwback type who put together some quality seasons in the early 2000s. His hiked-up socks and exaggerated windup (with the occasional double-clutch) earned him a memorable presence in a game quickly evolving to favor big guys with big stuff.

For a pitcher reliant on unpredictability and some casual moxy, adding a screwball to the mix is only fitting. Byrd was willing to take any edge he could get when he needed it, remarking, “Al Nipper taught me how to throw a screwball when I lost my changeup in two games; he got up on the mound and showed me how to do it.”18

Central to a pitcher’s screwball is his origin story with the pitch: 1) who showed it to him 2) what went wrong to make him want to throw it. You’ll never hear a pitcher’s regaling tale about where he learned how to throw a fastball.

In Byrd’s case the screwball was never a go-to. Only a temporary measure. More often than not the screwball was never anything more for a pitcher.

More pitchers who have thrown screwballs

In his A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches, Kepner also names:

- Fernando Valenzuela

- Juan Marichal

- Mike Norris

- Tom Browning

- Jim Mecir

- Mike Marshall

- Cliff Melton

- Harry Brecheen

- Luis Tiant

- Verdell “Lefty” Mathis

- Ralph Terry

- Frank Edwin “Tug” McGraw

- Willie Hernandez

- Mike Cuellar

- Clyde Wright

There are undoubtedly many others like Byrd who have dabbled with the screwball but never featured it.

Oliver Drake?

The wonderful Oliver Drake turned some heads with this delivery:

This pitch might have broken physics. pic.twitter.com/9M62Y5gzRt

— MLB (@MLB) July 21, 2019

Given the speed of this pitch – in the low 80s – in comparison to Drake’s high 80s fastball, this looks a lot more like a splitter than a screwball. You’d expect a little less velocity from a screwball. However, Drake’s extreme over-the-top delivery on top of apparent pronation upon release screams screwball. If anyone could twirl a screwball offhand it would be Oliver Drake simply because of his natural throwing motion.

Why does throwing a screwball hurt your arm?

A question that makes many baseball historians cringe. Many would challenge the premise. Let’s summarize the two schools of thought:

- Yes, throwing a screwball hurts your arm. You are making your arm do something so unnatural you can only hurt yourself. It’s wrong. It’s backwards. It feels funny when you do it—duh. Are we supposed to ignore the ridiculous correlation between heavy screwball use and serious arm/shoulder injury? You can count the number of pitchers who featured the screwball consistently on one hand, and pretty much all of them are long dead.

- No, throwing a screwball doesn’t hurt your arm. There is no hard evidence to suggest pronating the arm is any more harmful than the regular throwing motion. Hundreds of pitchers who have never pronated go under the knife for Tommy John and succumb to a number of different physical ailments every year. The pitching motion is unnatural no matter how you do it, and if your mechanics aren’t impossibly perfect and repetitive you won’t escape a long career without wear and tear.

Throwing a screwball is something like throwing sidearm or submarine-style. Because it looks and feels so that’s gotta hurt, confirmation bias clouds the conversation and muddies the waters.

Mike Marshall threw screwballs for 14 years. Between 1971 and 1974 he documented every pitch he threw: 39% screwballs, 34% fastballs and 25% sliders.19 Marshall concocted a full-blown methodology for pitching mechanics.20 Here’s a guy who isn’t concerned about the potential health risk of throwing the screwball as long as you do it the right way. He’s got all sorts of opinions.

Others weren’t so lucky. Carl Hubbell was a physical train wreck by the end of his career. Many others noted the discomfort of throwing a screwball and how they could only throw it so many times per game.

I’ll irresponsibly speak beyond my paygrade: it’s like any pitching motion. if you do it right, you won’t hurt yourself. If you do it even a little wrong, or do it way too much, you might wreck your arm. That’s not very scientific, but I’m betting it’s closer to the truth than a blunt yes/no answer.

Will the screwball return? Don’t hold your breath.

The screwball has been mostly relegated to the arena of softball, blitzball, wiffle ball or WII sports—or as an easter egg for a very specific audience of baseball fans who fired up Dragon Quest 5. It pops up here and there with an obscure pitcher from time to time, but it’s been a long time since a front-line quality pitcher routinely featured the pitch: Fernando Valenzuela, Warren Spahn, Christy Mathewson, Carl Hubbell. You’ve gotta go back a ways.

For the most part a screwball is a unicorn or tracking anomaly. Brent Honeywell remains a hopeful to carry the torch and feature the pitch, but after two separate elbow surgeries, the likelihood of his return and a long MLB career continues to slip.

References & notes

| 1 | “Screwball,” Wikipedia. Accessed July 13, 2019. Link. |

| 2 | This is Brent Honeywell’s grip (approximately, I think he has bigger hands). See it here along with some good GIFs and analysis. Eno Sarris, “Rays Prospect Brent Honeywell on Screwballs and Command,” Fangraphs. November 8 2016. Link. |

| 3 | This is pretty close to Hector Santiago’s screwball grip. Bruce Schoenfeld, “The Mystery of the Vanishing Screwball,” The New York Times Magazine. July 10 2014. Link |

| 4 | Bill James and Rob Neyer. The Neyer / James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 52. |

| 5 | Ibid. |

| 6 | Baseball, Inning 2: Something Like a War. Directed by Ken Burns. The Baseball Film Project, Inc., 1994. |

| 7 | Ibid. |

| 8 | James, Bill. 2001. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York, New York: Free Press. 851. |

| 9 | Baseball. Ken Burns. |

| 10 | Ibid. |

| 11 | Tyler Kepner, A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches (New York, Doubleday, 2019), 159. Kepner devotes a whole chapter to the screwball, and Mathewson is suggested early and often as the screwball’s primary representative. |

| 12 | Ibid 158. |

| 13 | This statement is delivered emphatically, but there is an educated disagreement on the subject. See Warren Corbett’s piece entitled Hubbell’s Elbow: Don’t Blame the Screwball in the Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal: Link. |

| 14 | Kepner, A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches, 157. |

| 15 | Marc Topkin, “Rays prospect Brent Honeywell out for season after fracturing elbow throwing pitch,” Tampa Bay Times. Jun 9 2019. Link. |

| 16 | Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer / James Guide to Pitchers, 390. |

| 17 | Kepner, A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches, 153. |

| 18 | David Laurila, “Prospectus Q&A: Paul Byrd,” Baseball Prospectus. Oct 5 2008. Link. |

| 19 | Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer / James Guide to Pitchers, 294. |

| 20 | See how deep the rabbit hole goes. Link. |

Recommended reading

These books were instrumental in the development of this article. All of them contain much more detail about the history of the screwball and its few practitioners.

James and Neyer collaborate for this handy historical compendium on baseball pitches and their practitioners. There are a few hundred pages’ worth of quickfire summary of the repertoire of pitchers both legendary and obscure.

A superb combination of encyclopedic comprehensiveness with the conversational feel like shooting the breeze over a couple beers. You’ll find yourself regularly plucking it off the shelf.

The bible of baseball books. James’ epic historical baseball abstract is a search engine on your shelf. Also—ensure 1) your shelf brackets are mounted on studs or 2) you place the book in a ground storage unit. This is a cinderblock.

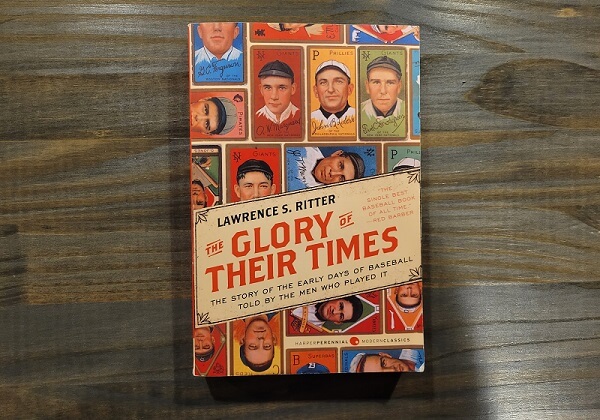

The volume contains just about everything you would want to know about the history of baseball, featuring chapters devoted to each decade from the 1870s through the 1990s.

Sure to become a classic, must-own. This book exhibits true joy for the game, featuring memorable anecdotes and quotes from some of the game’s best. Chapters are sorted by pitch type, offering peaceful periodic pleasure for baseball readers with small windows of free time.

Simultaneously a wonderful repository of information and a creatively weaved story of the game we revere. This book is delightful.

* Editor’s ask: if you’re interested in purchasing any of these books, please consider clicking the big gold “buy” button before your purchase. It really helps me keep this website ad and obnoxious-pop-up free.

The latest articles

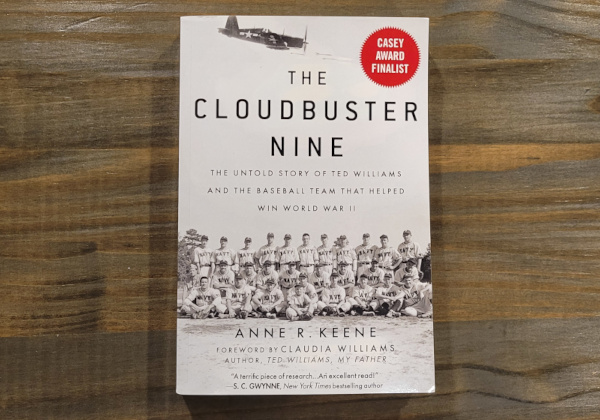

Book Review: The Cloudbuster Nine - by Anne R. Keene

by Fred Hofstetter on January 30, 2024Keene's comprehensive book tells several stories behind the V-5 Pre-Flight School in Chapel Hill, North Carolina: home to one of the rarest, greatest baseball teams in American history.

Book Review: The Glory of Their Times

by Fred Hofstetter on February 11, 2023There's good reason why The Glory of Their Times appears on every "best baseball book of all time" list you'll find anywhere.

Book Review: Future Value - Eric Longenhagen & Kiley McDaniel

by Fred Hofstetter on January 8, 2023Discover how amateur and pro baseball scouting is done, how departments are built, and how organizations find talent in Future Value.

Baseball players wear hats because wearing a hat is correct

by Fred Hofstetter on April 9, 2022Practicality explains why baseball players may want to wear a billed cap. But why does every player always wear a hat? Because it’s the right thing to do.